THE NATURAL POSITION FOR THE ARMS

As a movement researcher and educator, I have encountered a range of descriptions for the optimal resting position of the arms, from positioning where the thumbs point outwards, to the thumbs pointing forward, to the thumbs pointing inward. The graphic at right is a good example of how arm position influences posture. The outward-pointing thumbs lead to a tight back and excessive spinal curvature.

It is reasonable to posit that the resting position of the arms would be at the mid-point of their rotational scope. A simple exercise reveals where this point is:

Standing, rotate your arms outward to their end-stop. Note where that is, fully rotate them inwards, and note that position. The normal resting position of the arms is in the middle and it is commonly found that the thumbs end up just in front of the thighs.

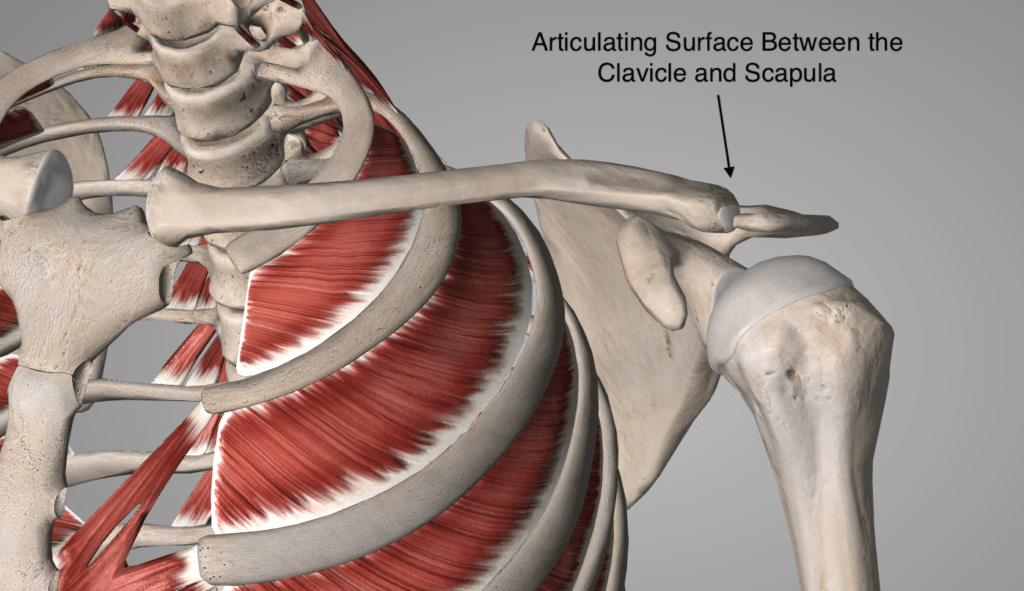

My opinion is that the confusion about the proper positioning of the arms originates from an anatomical misperception. It is common to consider the arms as starting from the shoulders.- comprising an upper and lower arm. However, the arm comprises three kinematic links that include the Clavicle, connecting the shoulder to the Sternum at the front of the chest.

There is a post here discussing this interface between the arms and the central core of the body:

When the arm is pulled back so that its multiplanar axis of rotation at the shoulder aligns with the midline of the torso, the thumbs rotate outward and we tend to hold our shoulders in that position by tightening the back muscles. When this rotational axis aligns with the Clavicle’s mechanical centerline, the thumbs rest in front of the thighs and the arms simply hang off of the rib cage, held by the shoulder blades.

If we recalibrate to initiate arm movement from the front of the torso we might discover that our conception of the scope of arm movement accessible to us increases exponentially, relaxing our back muscles and bringing our center of mass forward off the heels of our feet.

A TENSIONAL JOINT

Another anatomical clarification regarding the shoulder is that it is almost completely a tensional joint. Our legs attach to our pelvis within a dominantly compressional joint that competently transfers the weight of our torso. However, weight-bearing is done tensionally in the shoulder, conceptually by cables instead of struts. This allows for the extreme degrees of freedom that this joint grants.

Many of us will tend to operate the shoulder as a compressional joint, like most other joints within our body. Because the shoulder operates in tension, it will tend to get tight if it is not stretched out. In other mammals, this is not an issue as they tensionally carry their weight through this joint (weight “hangs off” of the foreleg). For us, having employed our forelegs otherwise means that it can be helpful to find ways to lengthen out the clavicle/shoulder/elbow complex habitually. This can be as simple as just grabbing a doorknob and leaning away from the door.

The blog posts in the TENSEGRITY AND CONNECTIVE TISSUE category explore tension/compression dynamics in biological systems in some detail.

This post explores the interplay between arm kinematics and the Lymphatic System:

THE LYMPH SYSTEM AND HANGING BY THE ARMS

HUMANOID ROBOT DESIGN

It is this writer’s, opinion that one reason that movement in the current crop of humanoid robots seems intrinsically artificial is that the arms are configured with 2 kinematic links originating from the shoulder rather than the three that we have been anatomically gifted. If you observe the arms closely you can see the reason these movements seem unnatural is because movement originates from the shoulder.

There is also a design preference for robotic gait employing stance mechanics (ball and heel simultaneous contact) instead of forefoot gait. The functions of the foot are discussed in this post:

THE FOOT – FUNCTION FROM STRUCTURE